The wall of the Egyptian palaces was called the serekh. The serekh glyph was one of the devices in which the name of the king was written. Another device was the more familiar cartouche. The sides and “frame” of the serekh probably represent walls as seen in a plan, while the entire symbol represented the walls of the royal palace or the city in which the king lived as the incarnation of Horus.

Royal palaces housed apart from the pharaoh’s main family, his secondary wives, concubines, and their offspring, also a small army of servants. The whole compound was enclosed and separate from the rest of the capital, albeit close to suppliers of services, temples and the seat of the administration.

From the New Kingdom period, some palace buildings remain. From the 18th Dynasty, there is the Malkata Palace, built for Amenhotep III, located south of his mortuary temple on the West bank of Waset (Gr: Thebes, modern Luxor). Then there are two of the five palaces built for Akhenaten at Amarna: the North Palace and the Great Palace.

From the 19th Dynasty and the Palace of Merenptah at MenNefer (Gr: Memphis), a throne room has been dug out by the University of Philadelphia. And from the 20th Dynasty, there are the remains of Medinet Habu, the palace of Ramesses III.

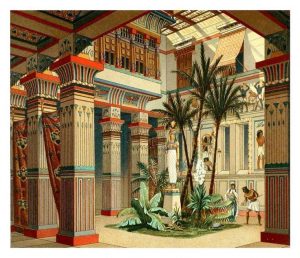

The palaces in ancient Egypt and temples would have acted as elite theatres of power, and the objects in them as the visible signs of power. The ancient Egyptian palace furnishings have not survived, even at better-known sites such as Amarna and Malqata.

Unlike the temples which were, at least from the outside, mainly symmetrical, Egyptian palaces were at times a conglomeration of functional units not hidden behind a unifying façade, even when they were built by just one pharaoh and were not the result of successive builders adding onto an initial building.

Akhenaten’s palace, the residence of the royal family was separated from the main palace by the main avenue, but connected to it by a bridge. Ay’s palace on the other hand – if we are to believe a wall painting in a tomb – was strictly symmetrical, and looked as much like a castle as like a palace.

Temple and Palace of Ramesses III lie south of Deir el-Medina and the Valley of the Kings, on the west bank of the Nile across from Luxor and Thebes. To the left, and extending behind the Amun temple, is the palace and mortuary temple of Ramesses III (ruled 1182-1151), the last great warrior pharaoh of Egypt. Ramesses’ enclosure wall contains both his temple/palace and the temple of Amun so that Ramesses is symbolically “united with eternity in the estate of Amun.”